Think the history of Rome revolves around Roman emperors and popes? While important, they only tell part of this legendary city’s rich story. Read more here about Rome’s history written by a historian of Italy!

This article isn’t meant to replace a guided visit – quite the opposite! Reading up on an attraction will make a guided tour more memorable and interesting! You will impress your travel partners and engage more with the guide. Check out our guided tours of Rome!

A Short History of the Eternal City

Sure, you could study Rome just by recalling the long succession of Roman emperors and popes. Indeed, this is how many students, me included, first learned about the Eternal City. But Rome’s history is full of much more: myths, dynamic personalities, and breathtaking art and architecture.

This article’s purpose is to introduce Rome’s history through such narratives. Rather than go chronologically through emperors and popes, we’ll follow a timeline shaped around major events and important historical figures. As they say, one lifetime is not enough to see all Rome has to offer. The same is certainly true of telling the city’s whole story in a short article. Hence, this is a brief history of Rome.

So, let’s be on our way!

C. 753 BC-509 BC

Foundation | Regal Period | Epic Myth

Rome’s story begins not with Romans, but with Etruscans…technically. That is because historian Simon Jenkins explains scholars recognize the existence of Roman monarchs of Etruscan and Corinthian origin. However, to get to this point we are glossing over a huge part of Rome’s founding myth.

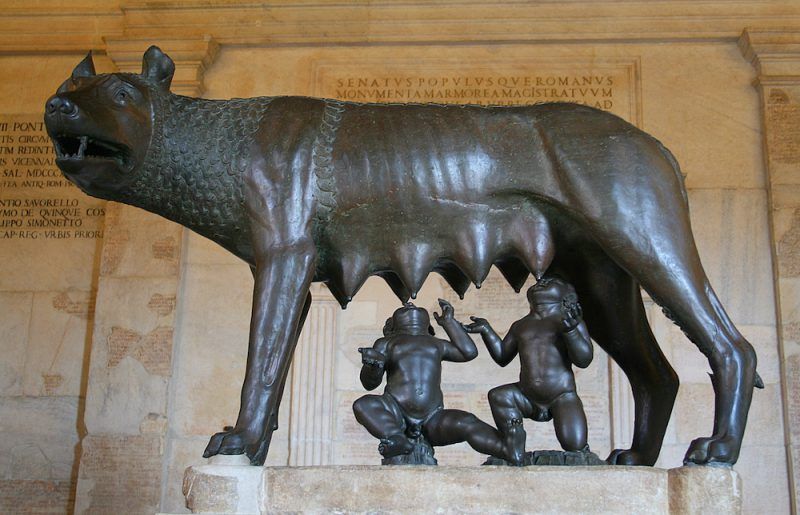

And as you might know, that myth goes back to a she-wolf nursing brothers Romulus and Remus in c. 753 BC. However, according to scholar Richard A. Ring, an early city likely formed in the 6th century BC, under the influence of nearby Etruscan city-states. Furthermore, historian Christopher Kelly says that under a series of monarchs, (the last three probably Etruscans), Rome emerged as a major player in central Italy.

At the same time, scholar Christopher Hibbert says that society became split between the patrician and plebian classes during the regal period. As a result, patricians and plebians wrestled for power and influence over much of the early Roman Republic’s history.

Moreover, historian Simon Jenkins explains that by the 5th century BC, both Rome and Athens experienced sweeping political change. Jenkins says that as Athenians cast off aristocracy in favor of democracy, the Romans drove out a king for a republic.

c.509 BC-250 BC

Republic Rises | Rebuilding | Control of Italy

And Rome did become a republic in c. 509 BC. However, historian Jeremy Black says the more reliable date is 507 BC. This date comes from the historian Polybius and well-informed Greek sources. Regardless, the republic’s rise is a key moment in Rome’s story.

Rome endured a severe disaster in the form of a Gallic siege in 390 BC. In fact, as scholar Richard A. Ring points out, only the Capitoline Hill remained in Roman hands after seven months. Eventually, the Gauls withdrew, but not before much of Rome lay in ruins. As a result, historians including Livy describe a frenzy of building activity. Arguably the most significant construction of that time involved impressive, fortified walls.

A rejuvenated Rome soon expanded its power in Italy. In fact, according to historian Jeremy Black, by 250 BC Rome emerged as the dominant power in Italy. Rome thus continued its conquest beyond Italy’s shores. Furthermore, at this point we find Rome embroiled in a series of conflicts with Carthage. At this stage, Rome is on the march, expanding well beyond the boundaries of a republican city-state.

250 BC-60 BC

Growing Power | Carthage | Conquest

Although the Punic Wars against Carthage began in the 260s BC, the rivalry heated up in the 240s. Moreover, the evolution of this conflict with Carthage reveals Rome’s rise as a major Mediterranean power. For instance, historian Simon Jenkins says that in the 260s and 250s, Rome’s infantry prevailed but Carthage’s navy remained dominant. However, by 241 BC Rome’s navy finally matched that of the Carthaginians.

You could say the Romans did their homework and soon surpassed their rivals for control of the Mediterranean. Rome’s road to Mediterranean conquest passed through two more wars with Carthage, as well as conflicts across Greece and Asia Minor. However, as historian Christopher Kelly reminds us, Rome’s conquests did not always proceed smoothly.

For example, historian Jeremy Black describes the campaigns of Carthaginian commander Hannibal. Black says this key general did well against the Romans in Spain and proceeded to complete the daunting task of crossing the Alps into Italy. As a result, historian Simon Jenkins explains Hannibal’s force crushed the Romans at Lake Trasimene in 217 and Cannae in 216.

Despite these crushing defeats, Rome soon bounced back to defeat Hannibal’s Carthaginians. Eventually, Carthage itself faced destruction at the hands of Rome in 146 BC. With mounting wars and victories, Roman leaders gathered increasing power and influence. Moreover, as historian Simon Jenkins explains, Roman generals governed conquered provinces. As a result, these generals earned the loyalty of their legions and wrestled for influence in Rome. Our next topic explores the most famous example of this kind of political conflict in Rome.

60 BC-44 BC

Chaos | Rivalry | Caesar & Pompey

We’ve reached a period in Rome’s story so dramatic it continues to fascinate. It certainly captivated William Shakespeare and generations of Hollywood writers. Our story begins with a battle of egos between Roman military heroes eager to secure further influence in Rome. The two men in question are Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey) and Gaius Julius Caesar. Their rising conflict according to historian Simon Jenkins is emblematic of corruption and declining faith in Rome’s republican institutions. As in many cases in history, the victor secured the upper hand through an appeal to populism.

Indeed, as scholar Christopher Hibbert explains, Pompey in the 50s BC became a rallying figure for Rome’s patricians and those concerned with preserving the status quo. On the other hand, despite coming from one of Rome’s oldest families, Caesar positioned himself as a man of the people. Moreover, as historian John Hirst says, Caesar’s victories in the Gallic Wars (58-50 BC) made him popular. Caesar and his legions bided time in Gaul before confronting Pompey.

Although Pompey effectively ruled Rome in 50 BC, Rome’s Senate ordered that both he and Caesar disband their legions. However, as historian Simon Jenkins says, Caesar disregarded this and dramatically “crossed the Rubicon” into Italy in 49 BC. As historian Jeremy Black explains, Caesar’s act was bold and illegal for a Roman general.

Caesar’s act led to a battle royale between his legions and those of Pompey. Historian David Gilmour says by 48 BC Caesar crushed Pompey’s forces and chased him from his base in Greece to Egypt. Caesar’s victory over the soon-to-be assassinated Pompey secured power in Rome. However, historian Simon Jenkins explains by the Ides of March in 44 BC Caesar fell victim to a senatorial conspiracy led in part by his former colleague Brutus.

44 BC-37 AD

Empire | Augustus | Pax Romana

Caesar’s assassination in Rome did not secure stability for the city. On the contrary, scholar Christopher Hibbert says political conflict intensified. This battle for Rome continued in the form of one of Caesar’s former lieutenants, Mark Antony, and Caesar’s young nephew and adopted son, Octavian.

Despite their differences, the two cooperated to defeat the legions of Caesar’s assassins at Philippi in Greece in 42 BC. However, the frenemies soon fell out with dramatic consequences. With victory at Actium 31 BC, historian Christopher Kelly tells us Octavian assumed control of what would become the Roman Empire.

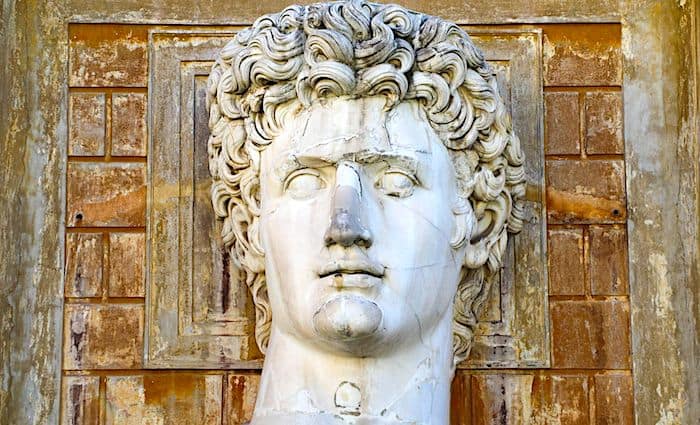

And that empire had an emperor named Augustus (the guy formerly known as Octavian). However, as historian Thomas Cussans tells us, Augustus spurned the title “emperor,” preferring instead to be seen as “first citizen” for four decades. Moreover, historian Simon Jenkins points out that Augustus did not really create the Roman Empire in geographic terms. In fact, as we’ve seen, Rome conquered vast territory during the republican era. Augustus however, according to Jenkins shrewdly consolidated these vast possessions.

In fact, historian Thomas Cussans says Augustus presided over an extended period of peace and prosperity within Roman provinces. Called the Pax Romana (Roman Peace), this time witnessed the expansion of commerce, public building activity, population growth, and stability. Importantly, by the end of Augustus’ life in 14 AD, historian Christopher Kelly says he ensured stability and continuity through the rise of his stepson, Tiberius.

37 AD-286 AD

Zenith | Splendor | Overstretched

After Tiberius, imperial rulers rose and fell at an astounding rate. Yet, despite instability, the Roman Empire remained a dominant power. Some of the most famous imperial characters include Caligula, Claudius, and Nero. Historian Simon Jenkins argues one common theme in addition to instability involved persecution of the adherents of the nascent Christian faith.

Imperial power spawned imperial splendor in the form of public works and spectacles across multiple dynasties. Arguably the most famous of such splendor is Rome’s Colosseum. As historian Christopher Kelly tells us, Emperor Titus inaugurated the Colosseum in 80 AD.

Military conquests continued under successive imperial dynasties. The Antonine dynasty which succeeded the Flavians like Emperor Titus part marks the highpoint of Rome’s territorial reach. In fact, historian Simon Jenkins mentions Emperor Trajan’s victories (98-117) meant Rome stretched from Britain to Armenia and from Mauritania to Mesopotamia. Furthermore, scholar Richard A. Ring says Trajan presided over impressive urban planning evident in the forum he built.

However, much of Imperial Rome’s power and strengths became situated outside the walls of Rome. At this point, we must distinguish between the history of Rome, the city, and the Romans. For instance, archaeologists Christopher Mee and Anthony Spawforth say some emperors traveled the empire extensively. Moreover, many emperors hailed from different parts of the empire. For example, Mee and Spawforth tell us about Hadrian (r. 117-138 AD), builder of the famous wall in Britain, and many public buildings in Athens among other projects.

Heading to Rome? Your experience will improve by leaps and bounds with a local guide. Check out our top-rated Colosseum tours for more!

286-476 AD

Restructuring | Constantine | Christianity

However, by the mid-280s AD, Roman power waned and prompted restructuring. In fact, historian Simon Jenkins explains by 286 Diocletian set out a plan to partition the empire. Historian Christopher Kelly says Diocletian ruled the east and Maximian the west. However, as historian John Hirst tells us, Maximian governed from Milan, not Rome.

Indeed, by the 3rd century AD, Rome’s glory days fast faded. In fact, scholar Richard A. Ring tells us that Constantinople’s (today’s Istanbul) founding only confirmed Rome’s loss of political prestige. However, the namesake of that city, Emperor Constantine I sponsored a resurgence of public life in Rome. According to scholar Richard A. Ring, Constantine did this through his sponsorship of Rome’s Christians and the restoration of numerous public buildings in Rome.

Christianity though, as we’ve seen emerged long before Constantine’s reign and embrace of the faith. Despite the official shift in the treatment of Christians, scholar Christopher Hibbert says 4th century Rome remained a distinctly pagan city. Nevertheless, Constantine’s actions laid the foundations for Christian and papal Rome of the medieval and modern eras.

476 AD-800 AD

Imperial Collapse | Disorder | New Rulers

Rome endured numerous raids and attacks from the Visigoths and Vandals in the 400s AD. Scholars traditionally mark the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD. According to scholar Richard A. Ring, this resulted from the rise to power of the first barbarian king of Italy, Odoacer.

Although Romans no longer ruled Rome, a Roman Empire still existed. As historian Simon Jenkins explains, the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire under Justinian I sought to restore imperial authority in Italy during the 6th century AD. Justinian’s campaigns, according to scholar Christopher Hibbert proved disastrous for Rome. Sieges devastated Rome, crippling infrastructure, and forcing many people to flee or perish from various privations. By the end of the 6th century, Pope Gregory I controlled Rome. As historian Simon Jenkins explains, this ushered centuries of papal authority in Rome.

800 AD-1420 AD

Papal Power | Charlemagne | Radicals

Once again, Rome served as the backdrop for a pivotal moment in history. As historian Jeremy Black explains, Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne “Roman” emperor in 800 AD. However, Black continues, Aix-la-Chapelle (Aachen, present-day Germany) became the center of Charlemagne’s empire and not Rome. Yet, with the power of successive Holy Roman emperors ruling from north of the Alps, popes gradually built a state for the Church.

Although today only Vatican City remains, the papacy once controlled swaths of mostly central and northern Italy. As a result, historian John Hirst says popes ruled from Rome (mostly) over both a spiritual and temporal empire until Italian Unification in the 19th century.

While popes carved out power, Rome also witnessed the rise of a secular civic government by the 1100s. Thus, a power struggle between the papacy and secular leaders is a common theme in Rome’s history through the 20th century. In fact, as scholar Christopher Hibbert explains, you’ll find many examples of secular civic leaders challenging papal authority. One famous example is that of Cola di Rienzo.

Cola di Rienzo led a brief popular rebellion against Pope Benedict XII in 1347. However, Cola di Rienzo was not just any anti-papal agitator. In fact, as historian David Gilmour notes, this Roman rebel styled himself “Tribune of Rome” in the ancient republican fashion. Although unsuccessful and executed, Cola di Rienzo became a popular hero of later generations of political leaders who sought to undermine the power of the popes.

1420 AD-1700 AD

Renaissance | Counter-Reformation | Bernini’s Rome

Scholar Richard A. Ring says we can trace the origins of Rome’s Renaissance to the arrival of Pope Martin V in 1420. Ring explains that Pope Martin V also firmly established the absolutist rule of successive popes until 1870. Moreover, art historian Ian Chilvers explains that Rome’s Renaissance zenith came during the papacy of Leo X (1513-1521). According to Chilvers, Leo played a crucial role in fostering Renaissance art and architecture through his patronage of Michelangelo and Raphael among others.

Despite the city’s growing wealth and stability under the popes, it continued to weather challenges. Among these according to historian John Hirst was the 1527 sack of Rome by the army of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. For scholar Richard A. Ring, the 1527 sack of Rome marks the end of the city’s Renaissance age.

However, even during the rule of aggressive Counter-Reformation popes, artists and architects flourished in Rome. In fact, Pope Sixtus V (1585-1590) sponsored expansive urban development projects. For example, scholar Christopher Hibbert says Sixtus renovated papal palaces of the Vatican and Quirinal, built the Vatican Library, organized new public squares, and oversaw the completion of St. Peter’s dome.

Arguably the most significant figure in the realm of art and architecture in this period is Gian Lorenzo Bernini. According to art historian Franco Marmondo, a young Bernini took Rome by storm between 1622 and 1625. In that period, art historian Ian Chilvers says Bernini produced sculptural masterpieces for the powerful Borghese and Barberini families including Apollo and Daphne. Moreover, according to scholars including Franco Marmondo, Bernini produced the quintessential work of Counter-Reformation art, the Ecstasy of Saint Theresa.

1700 AD-1870 AD

Grand Tour | Road to Unification | Mazzini & Garibaldi

Rome by the early 18th century attracted waves of northern European visitors on the Grand Tour. However, historian David Gilmour says that Grand Tourists explored a city in decline. Indeed, despite Pope Sixtus V and his ambitious urban renewal projects, successive popes failed to maintain the city. Disease, poverty, and neglect abounded. Moreover, as historian R.J.B. Bosworth says, ancient sites like the Colosseum continued to wither away.

Stagnation, however, gave way to political and social upheaval with the coming of the French Revolution. In fact, as historian Andrew Roberts explains, Napoleon brought sweeping change to Rome in 1798. Furthermore, historian David A. Bell says this began a time of conflict between Napoleon and the papacy. Eventually, Napoleon exiled and essentially imprisoned the pope. As a result, historian John Foot says the restored papacy after 1814 reacted harshly to any revolutionary sentiment.

However, such upheaval fueled Italian nationalism and dreams of a unified modern Italian state. Among the many leaders and architects of Italian Unification, two stand out in Rome’s story. The first of these is nationalist leader, philosopher, and agitator Giuseppe Mazzini. An eccentric figure who always dressed in mourning clothes for Italy’s sad fate, Mazzini inspired numerous uprisings. However, historian David Gilmour says Mazzini’s most famous revolt involved an effort to create a Roman republic in 1848-49.

While Mazzini provided the intellectual and emotional backdrop for unification, our next figure packed the punch. Indeed, Giuseppe Garibaldi could be described as a born revolutionary and fighter. Moreover, as historian Lucy Riall tells us, Garibaldi’s exploits became so famous internationally that we can consider him among the first modern celebrities. Unfortunately for Garibaldi and Mazzini, celebrity alone could not deliver victory over the pope and the 1848-1849 republic failed.

1870 AD-1945 AD

Capital City | Wedding Cake? | Mussolini’s Rome

While Mazzini and Garibaldi’s effort to create a Roman republic failed, the drive for unification continued through the 1850s and 1860s. In fact, historian Chris Duggan says by 1860-1861 a unified Italy had been achieved. However, notably, Italy did not yet include Rome which was still under papal control.

Yet, that would soon change. September 20 is an important date to remember in Rome’s history. On that day in 1870, Italian soldiers breached Rome’s walls and seized the city from the pope. Shortly thereafter, Rome became the capital of Italy. Thus, as scholar Christopher Hibbert explains, officials spent lavishly to make Rome appear a modern European capital city.

At the same time, Italian officials dedicated monuments in Rome designed to foster patriotic feelings for the young nation. For example, historian Aristotle Kallis tells us about the massive monument to Italy’s first ruler, King Vittorio Emmanuele II. Known as the Vittoriano, you may also know it by its nickname, the “Wedding Cake.” Although forever associated with Mussolini because of his regime’s preference to stage events there, the Vittoriano predates the rise of fascism in Italy.

Moreover, historian Emilio Gentile says Mussolini’s Fascist regime spared no expense when it came to attempts to emulate the Roman Empire. As historian R.J.B. Bosworth tells us, this took multiple forms including expansionist conflicts like the 1936 invasion of Ethiopia as well as massive urban development projects in Italy. Ultimately, Mussolini’s aggressive policies contributed to the regime’s fateful decision to align with Nazi Germany during WWII.

1945-Present

Postwar | Reconstruction & Integration | La Dolce Vita

Many areas of Rome sustained heavy damage during WWII. As a result, the war’s aftermath meant literally picking up the pieces and rebuilding what had been destroyed by bombing raids and street fighting. However, as historian Paul Ginsborg tells us, postwar reconstruction also meant expansion via new neighborhoods. Moreover, as historian Spencer M. Di Scala explains, an influx of migrants from southern Italy necessitated this urban expansion.

As Rome recovered and expanded after WWII, so too did the city’s place in the story of postwar Europe. For example, when we think about the European Union, our minds mostly turn to Brussels. However, today’s EU owes much to Rome. In fact, historians Simon Usherwood and John Pinder note that the 1957 Treaty of Rome established the forerunner of today’s European Union.

Above all, postwar Rome became the symbolic capital of all things glamorous about Italy. Whether people-watching in cafes or zipping around on Vespas, millions around the world fell for the culture emanating from Italian cities like Rome.

According to film scholar Lee Pfeiffer, this stems in no small part from Rome’s depiction in famous foreign and Italian films. While some movies, like Federico Fellini’s classic La Dolce Vita, did not seek to glorify this culture, they nevertheless fueled Rome’s popularity with tourists.

Now you’re ready to explore Rome!